Labyrinth of Desire

Katherine Ware, 2010

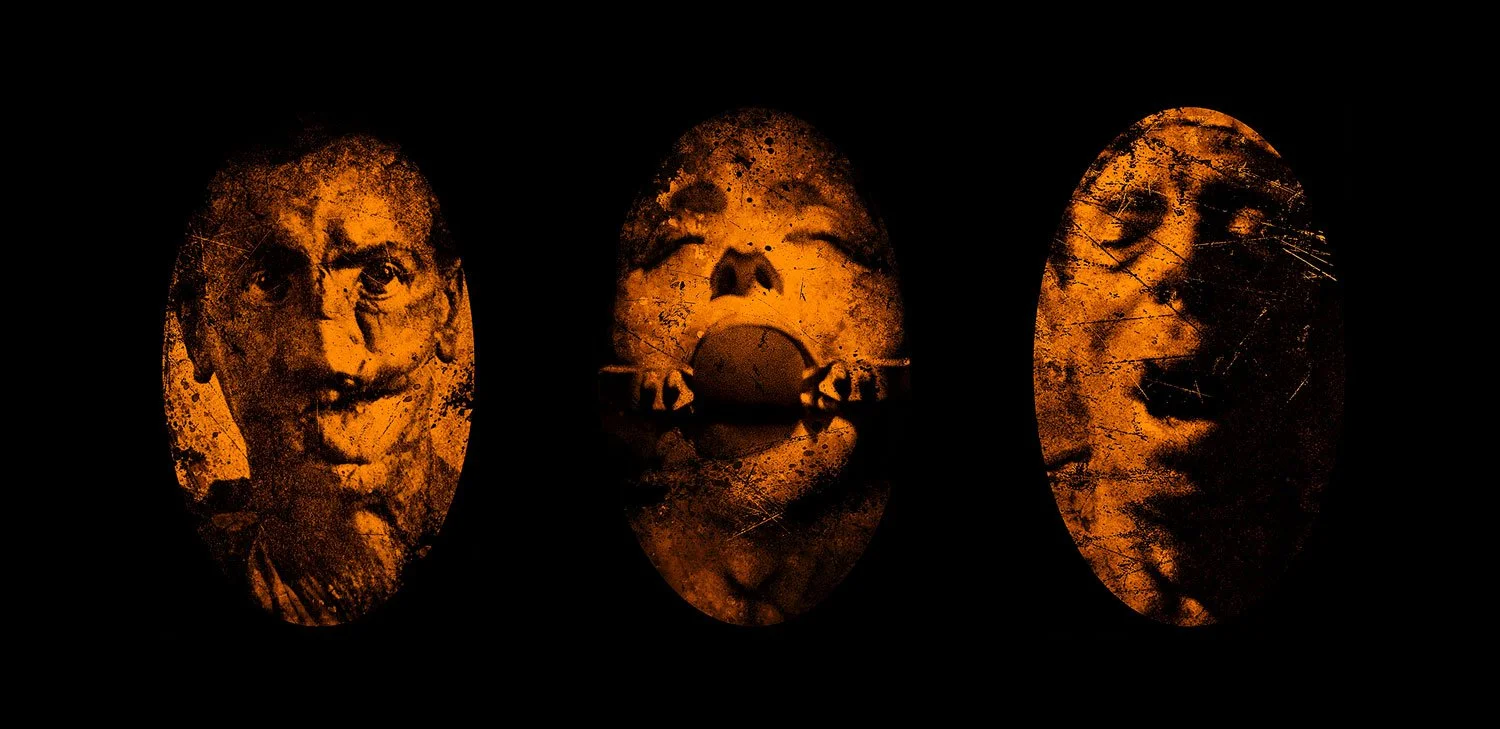

detail from fragments of a celestial abattoir

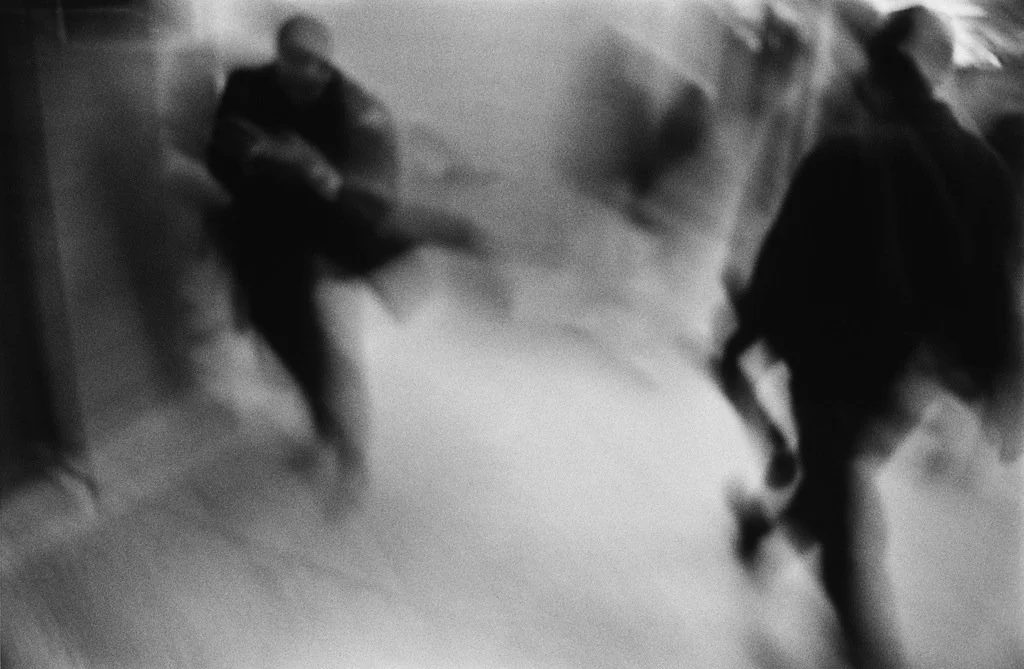

From the series Arena ©Frank Rodick, 2002

Katherine Ware is Curator of Photography at the New Mexico Museum of Art and has served as Curator of Photographs at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and Assistant Curator in the Department of Photographs at the J. Paul Getty Museum.

In this essay, Katherine Ware discusses Frank Rodick's work from 1991 to 2010. She wrote the text for the catalogue that accompanied the exhibition she also curated, Labyrinth of Desire: Work by Frank Rodick held at the Deborah Colton Gallery in 2010.

Copies of the original catalogue are available for sale through the Deborah Colton Gallery. A few signed copies are available: contact info@frankrodick.com.

We've walked on the moon, our species. We’ve filmed luminescent sea creatures in the ocean deep, peered into active volcanoes, and studied Antarctica before it melted away. But the human mind continues to be one of the most uncharted frontiers of all. From his beginnings as a photographer, Frank Rodick has consistently explored this terrain, breaching the crenellations of the cerebral cortex to probe the limbic system, where our animal selves hunker. A medium recognized for its excellence in recording surfaces, photography is a challenging tool for plumbing the recesses of the brain. However, because it so easily creates a mirror world, a place parallel to our own, photography is also adroit at recontextualizing recognizable subjects to create new meanings. Rodick exploits this paradox and, as his career progresses, continues to use techniques that sever images from conventional interpretation, pushing viewers to engage with them in a less straightforward manner. “As hallucinatory as they may seem,” Rodick writes, “the images I work to create are ones that feel to me more intimately real than our cursory experience of everyday life, and that give voice to the inner worlds that exist in each of us.”

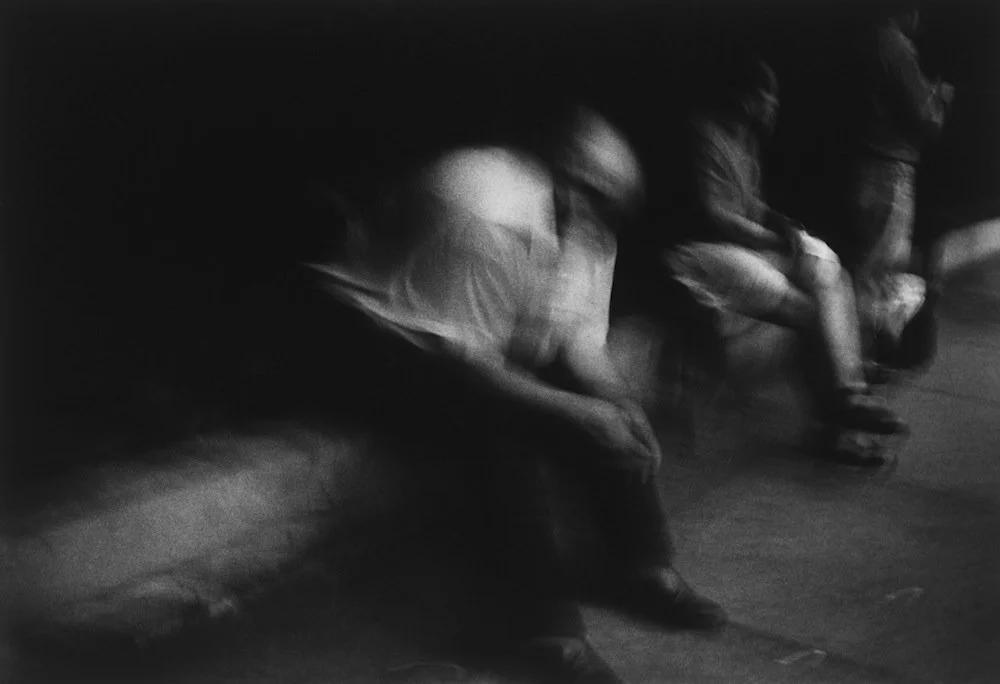

Liquid City

Rodick began his photographic career doing black-and-white street photography, which developed into the series Liquid City (1991–1999). Having grown up in Montréal where his parents owned a downtown book shop, the artist considers the cityscape his photographic starting point, a place where he was captivated by the diversity of human tableaux. To portray his subjective conception of city life as “an ongoing carnival of paradox, uncertainty, and restless solitude,” Rodick emphasizes the ebb and flow of its daily rhythms in the photographs, from commuters rushing through subways (untitled, no. 25; see carousel above) to people immobilized by having nowhere to go [untitled, no. 123]. The dynamism of the images elicits a physical empathy on the part of the viewer, as the denizens of Liquid City hurtle toward us or jostle past impatiently, engaging us vicariously in the urban tempo.

These qualities are conveyed by the artist’s masterful use of blur and distortion, which offer a compelling sense of animation and urgency, as well as reinforcing the unknowability of the fellow human beings in our midst. We are close enough to touch these people but they remain ciphers. We see exemplars, rather than individuals: the vendor, the commuter, the busker, the loner [untitled, no. 106]. Faces are obscured or exaggerated into a clownish leer, a mask of resignation, or else disintegrate altogether into the atmosphere [untitled, no. 46]. These untitled images were made in a variety of international cities, but Rodick does not identify the locations. This lack of geographical grounding suggests a global urban culture of anonymity and homogeneity, while reminding us that experiences ultimately take place in our internal landscapes, wherever we may be standing.

Overall, the impression is one of darkness, isolation and sometimes dread. In the background of one picture, an inky smear transmogrifies into a black dog attacking a man from the rear, the devil on his back [untitled, no. 40]. In another, a figure bundled against the weather takes on the appearance of a cowled skeleton, as though even the Grim Reaper walked among us, unnoticed in the crowd [untitled, no. 82]. Only a few playful children seem to escape the weight of existence in this body of work, perhaps a touch of nostalgia on the part of the artist.

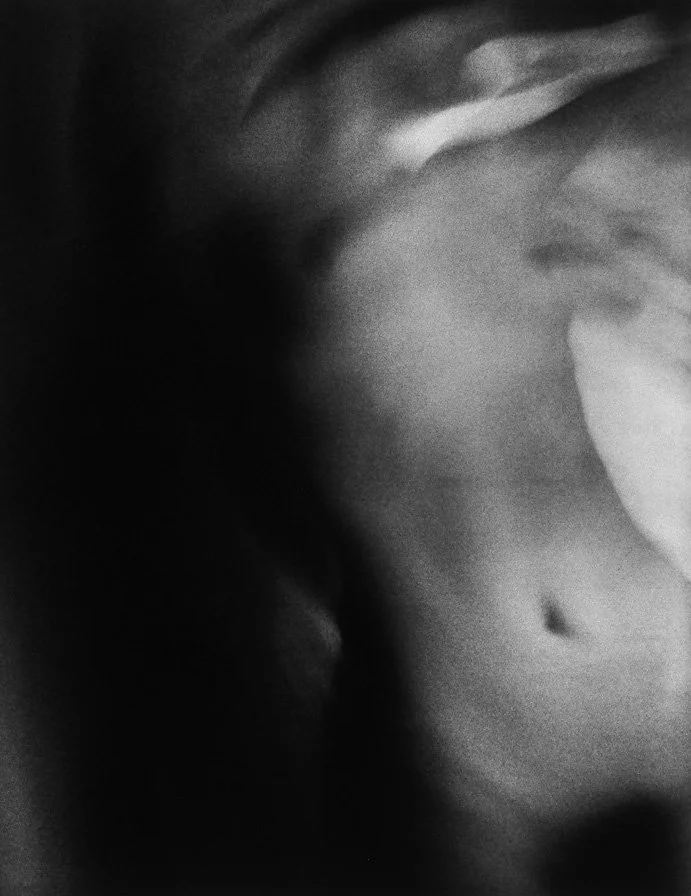

sub rosa

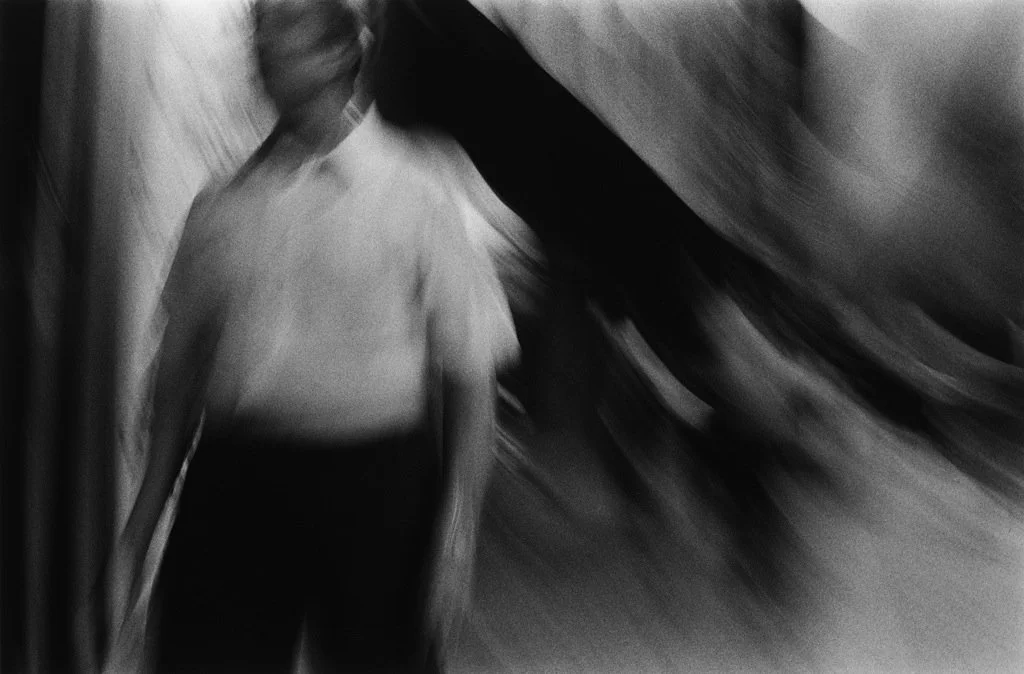

In a smaller, concurrent series of black-and-white photographs, sub rosa (1995–1997), Rodick moves into the studio to work with the classic genre of the female nude, bringing a freshness to the subject while again pursuing the theme of human insularity [sub rosa, no. 2; carousel above]. These photographs, made initially with expired Polaroid film, seek to evoke the artist’s experience of the paradox of intimacy and mystery between human beings, and specifically between the genders.

As in the Liquid City photographs, these images are filled with movement but are redolent with the presence of a sole figure. The artist has selected essentially frontal views of the model that emphasize the torso, creating a sense of close proximity between subject and viewer. The model’s interaction with the photographer becomes her interaction with us, and establishes a level of private engagement [sub rosa, no. 11]. We are alone with her, she advances and gyrates, reveling in her own body [sub rosa, no. 5]. A haze emanates from each of the figures, suggesting the force field of the female form and our powerful sensual responses to unclothed bodies.

Headless as they are, these women have presence, striding and swaying toward us, displaying flesh, but keeping us at the distance of an outstretched arm [sub rosa, no. 9]. They are not temptresses but more like fascinating enigmas. While the naked form suggests that all is revealed, its surface is mutable and we get no clues to the identity, thoughts, or feelings of these women. The title of the series, sub rosa (a Latin term referring to secrecy), underscores the tightly held nature of such revelations.

Arena

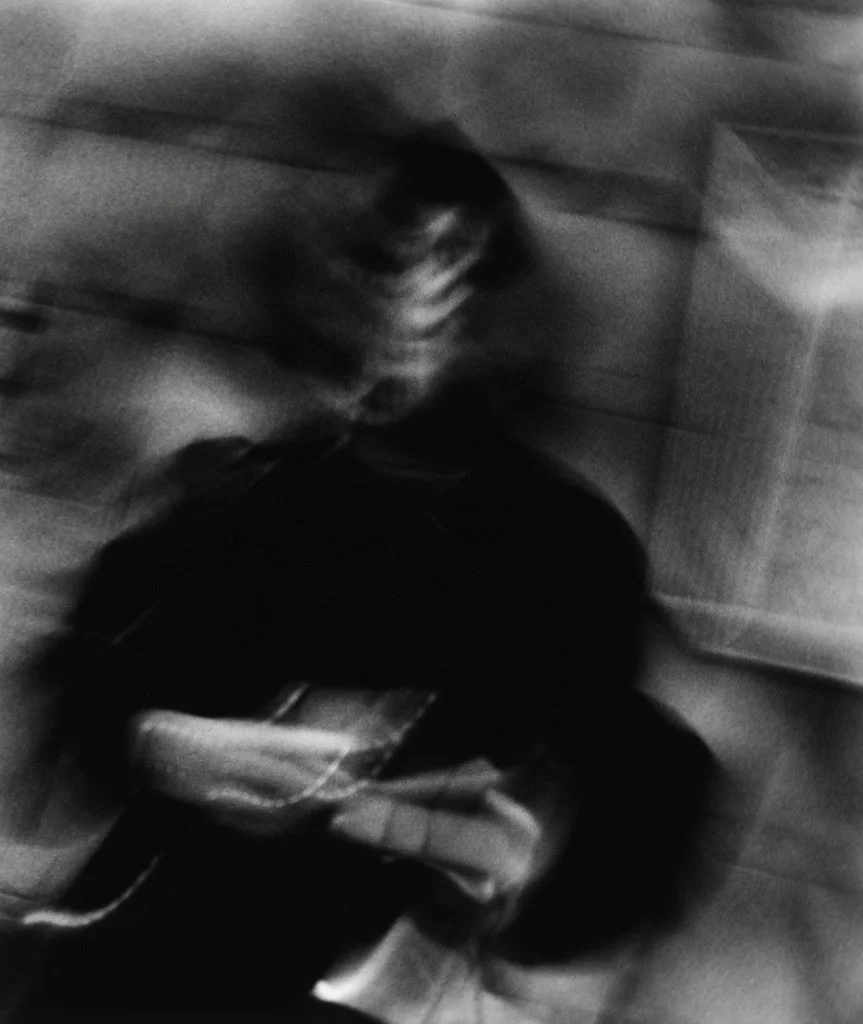

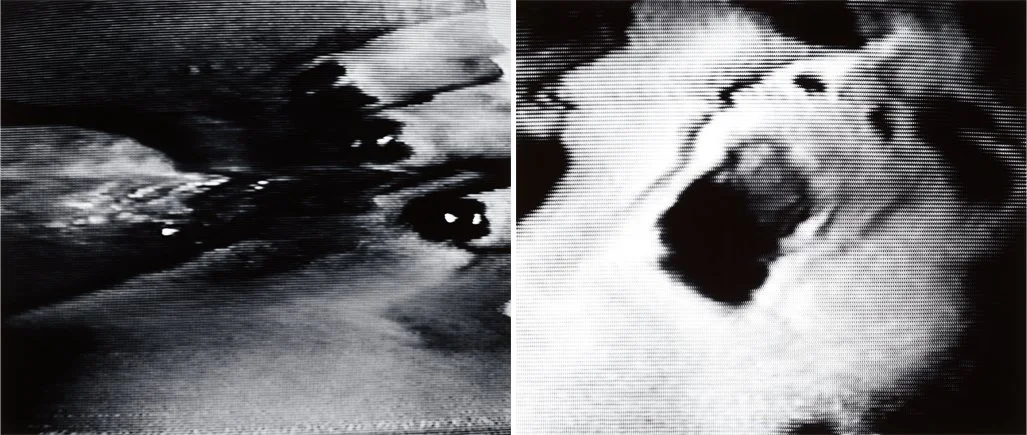

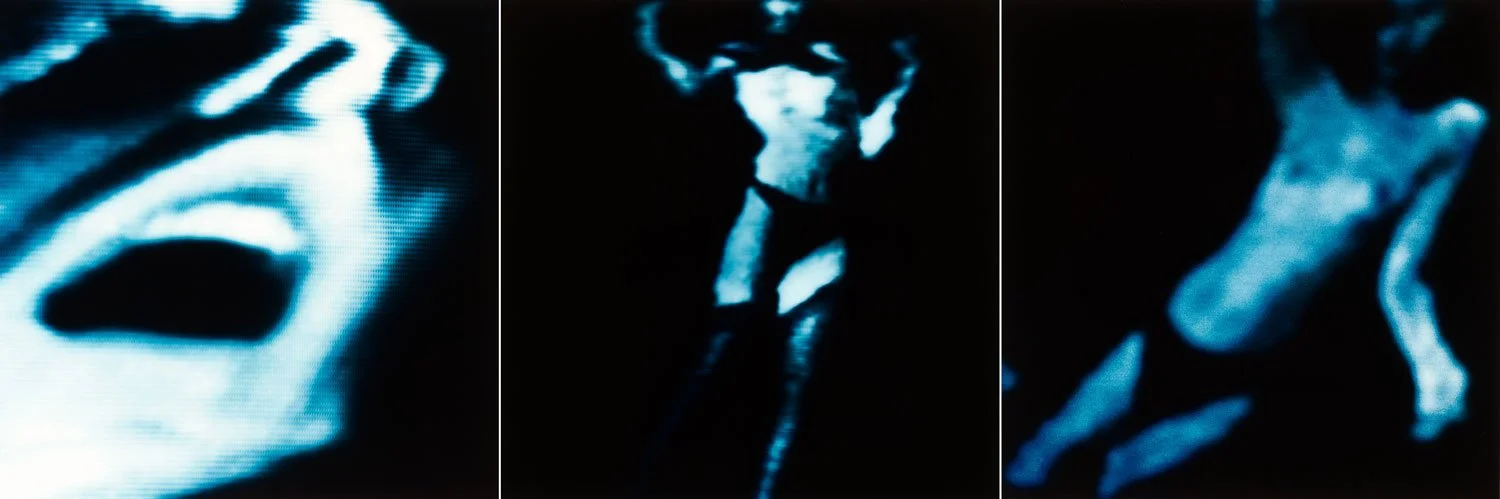

Having spent nearly a decade on street photography with one foray into the studio, Rodick shifts both content and technique in his next series, Arena (2002-2005). In his first two bodies of work, Rodick trained his camera on the human figure and employed a variety of methods to obscure the medium’s precision, emphasizing his interest in the subjective nature of reality and the emotional gulf between human beings. In Arena, Rodick pivots inward, looking beyond our insistently opaque exteriors to reveal the chaotic interiors they guard so closely. As the name Arena implies, Rodick offers an open space, a stage for the playing out of psychic dramas. The action in this Arena is purely psychological, although (as in dreams) it is expressed in human form, an essential referent in Rodick’s work.

This time, Rodick begins with video, using it to capture footage of live models and pre-existing images, such as movies from a television screen, which he further manipulates and combines to create the prints [3 a.m. (engram); first carousel above]. As in sub rosa and Liquid City, these images are not characterized by stasis, randomly snatched as they often are from low-resolution moving pictures. Degraded and imprecise, they reinforce our sense of being outside the boundaries of normal reality. The artist again harnesses the powerful associations of the mimetic image while always working to subvert the documentary quality of photography. Here, too, the approach approximates the vivid but indistinct quality of the fantasies and nightmares that play nightly in the private theatres of our minds [reveries (dusk)].

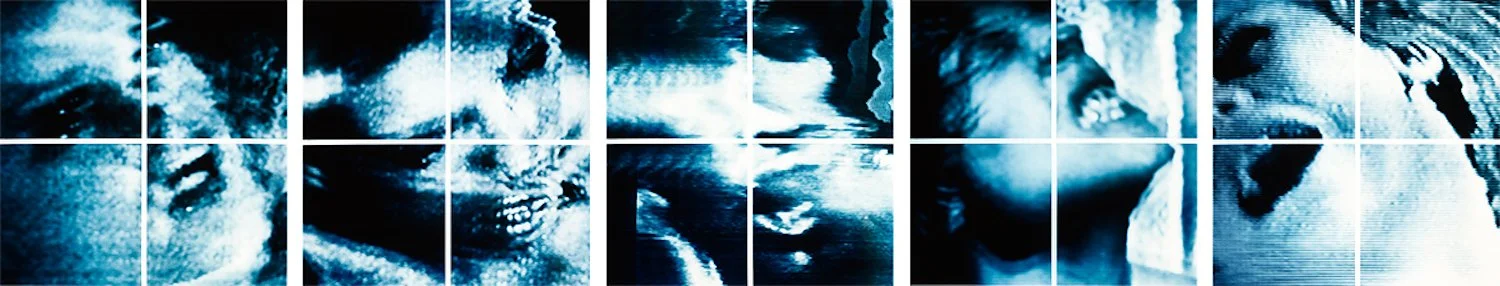

The individual images can be disturbing to view, showing bared teeth, a mouth in mid-scream, or fingernails like claws, all of which put the amygdala in our brains on high alert [untitled diptych]. We see details of faces for the first time in this work, and, far from being blank masks, these creatures in extremis exude urgent but unspecified emotions [porneia]. Ambiguity is central to these works, encouraging the active, subjective participation of the viewer. For some, they summon brutal images of violence, torture, rape. Rodick’s aim is not to call to mind any particular scenario, but these interpretations are valid insofar as the images are constructed with the ambition of eliciting a raw, unmediated response in viewers [memento of a third floor crucifixion (re-collection, no. 1); second carousel above]. This is claustrophobic work that reminds us in vivid terms that we are each alone with our passions and demons and that sometimes the two are hard to tell apart. Rodick is most interested in bringing to the surface the feelings and sensations buried deep within us, a viscous stew of baseness, ecstasy, and fear.

Titles become prominent for the first time in Arena, but they are as elliptical as the images. Rodick delights in prodding the dark chamber of the mind with the dark chamber of the camera, so instead of revealing the artist’s intentions, the titles simply add another ripple to troubled waters. “My hope is to create a kind of sensual directness in these pictures, a bypassing of the rational self that depicts, projects, and engages primeval emotions while addressing such fundamental issues as memory, eros, mortality and pain,” the artist writes. Using words like “reveries,” “memento,” and “fragments,” Rodick urges us toward a contemplative reading of the work. Other choices, such as "Porneia," “crucifixion,” and “abattoir” are more reactionary and easily trigger a gut response, although the latter two are complicated when placed in the context of the complete titles (Memento of a third floor crucifixion (re-collection, no. 3); fragments of a celestial abattoir.

Using color for the first time in Arena, Rodick tones some prints to amplify their emotional charge with the orange hue of corroded souls or the blue of a television screen flickering at 4 am [reveries (dusk); porneia; memento of a third floor crucifixion; la pucelle), to play against a more neutral grey. He also begins using multiple images within a single composition (diptychs, triptychs, polyptychs) arranged in a linear and usually horizontal manner that mimics a line of type. The format suggests an unfolding of events as well as something that can be read sequentially, engaging a temporal dimension. The multiple panels hold our attention as we make futile attempts to construct a meaningful narrative from a hermetic loop. As the series progresses, the artist begins working with the idea of a grid of images—culminating in fragments of a celestial abattoir [second carousel above]—and moves beyond a strictly linear format.

Faithless Grottoes

the longest night has twenty faces

decrement (all flesh/63 chambers)

Rodick uses the themes and techniques of Arena as a springboard for his subsequent series Faithless Grottoes (2006-2009), as can be seen in an arguably transitional piece such as Two figures, triptych no. 1 [see carousel above].

Taken as a whole, Faithless Grottoes is the most compelling, eloquent synthesis of the artist’s preoccupations to date. His use of found images, multiples, and selective color are familiar, but are used more freely and confidently in this engulfing, large-scale work. We see more interrelatedness in the images, moving us around the compositions. The increase in the number of images in a single composition gives the work a more filmic tone and a stronger illusion of narrative, though the tight mashup of pictures continues to resist rational storytelling. Rodick also intensifies his palette in this body of work, taking advantage of the more saturated reds, oranges, and blues of color photography. Titles are again a significant element and often refer to some of Rodick’s favored authors and poets, including Franz Kafka, Louis-Ferdinand Céline, J.M. Coetzee, and Paul Celan.

While Arena is tremendously atmospheric and suggestive, Faithless Grottoes presents somewhat more developed and individualized states. In The longest night has twenty faces [above], its title taken loosely from the poetry of Celan, Rodick combines four images of varying size and color. Three provide snatches of a figure – faces and hands – printed in a chill, ghostly blue that evokes the spirit world of memory. The atmosphere of loss radiating from these images is offset by a panel in the lower left corner of a man (or is it a woman?) furiously gnashing his teeth, the face flashing red. Without any clear storyline, the work clearly communicates the power of this rage and its terrible repercussions. In Rodick’s piece Room 36 (time on earth) [carousel above], a progression of events is also strongly implied. The title is derived from the name that the French writer Céline gave to his personal conception of hell as a banal, secular, and thoroughly human destination and condition. The artist’s visualization is far more menacing, however, with its fearsome orange overtones of entrapment, restraint, and predation.

The composition love [carousel above], on the other hand, while having no narrative thread, provides us with perhaps the clearest indication of subject matter in the artist’s oeuvre. In it, he juxtaposes five iterations of the same face, its shifty eyes deep in shadow and its lips parted. The title conjures up the brambled, contradictory nature of a common emotion, love, which can encompass jealousy, carnal lust, dominance, revenge, secrecy, humiliation, and a host of other things not found in valentines. Moving from left to right, we slam up against a dark patch at the end of the picture, perhaps standing in for the treacherous tar pit in which love mires its victims.

It is not uncommon for Rodick to use the same image in different compositions, but in some cases he has returned to a finished piece and reworked it into an alternate version. The Faithless Grottoes series reprises porneia, which originally appeared in Arena and appears in the later body of work as a triptych [carousel above]. The first piece [carousel in Arena section] is composed of five prints, toned a steely blue. Each shows a contorted face scored by perpendicular white lines, invoking windowpanes through which we surreptitiously glimpse something illicit. In the second incarnation, two faces from the earlier composition are magnified and joined with a new countenance; their facial contortions and the angle of their heads conspire to create a thrashing, flailing effect, with an overlay of black lines that remind us of the cross hairs of a scope or a weapon.

Even more gripping are the several works springing from Arena’s sixteen-image composition la pucelle (the maid), an affectionate nickname for the French historical figure Jeanne d’Arc. Three works sharing the title decrement— decrement, as triptych; decrement (All flesh/63 chambers) [above]; and decrement (tenebrae)—attest to Rodick’s fascination with her story (and Carl Dreyer’s interpretation of it in the film The Passion of Joan of Arc), based on her intense religious conviction and the dramatic heights and depths that developed from it. The searing orange hues and scorched blacks of these bravura images, along with the beseeching expression of agonized ecstasy on the woman’s face, dramatically convey the complexities of extreme emotional states and the uncertain boundaries between them.

Revisitations

Rodick’s most recent work, begun in 2009 and still underway, treats some of the ideas from Faithless Grottoes in a slightly more representational manner, relying less on dramatic juxtapositions. These color pieces, collectively titled Revisitations, hew to the artist’s usual palette and are much smaller and generally quieter than the imposing pieces in the previous series. In a drastic reversal of scale, these pictures are ideally meant to be held in the viewer’s hands, seen privately by one person at a time. Each print is encased in a wooden box with a lid, an elegant but spare container. The boxes recall the presentation of some of the earliest photographs made, daguerreotypes, which were customarily housed in palm-sized, velvet-lined cases. The artist also refers to nineteenth-century photography and cased images by vignettting several images and in the way he prints [carousel above], possibly to evoke a sense of elegy, memory, or loss.

The images themselves are especially gruesome, including a lynching, a mangled horse, and bared fangs. These are primarily found images, some of which have a more historical and documentary quality than Rodick’s previous selections. While the artist retains the technique of multiple, spliced images, he has, for the first time since Liquid City and sub rosa, maintained a consistent size for all the prints in this group. Instead of being about the bestial cesspool of our souls, these images appear to be about an actual hell on earth, human transgressions heinous enough to require a closed lid.

Even so, the lid opens. The witnessing of the malady of being human – in its fulsome range of extremes, contradictions, and complexities – is perhaps the primary motivation for Rodick’s work. His ruminations on the frantic lives going on behind our social facades lead not to redemption but back to the hard fact of itself. But the nihilism that oozes like blackstrap molasses from some of these pictures is not unrelieved by a tang of sweetness. The search for meaning, the drive to make sense of the fragments of our earthy abattoir, is as ineluctable a human trait as all the rest. “Perhaps in not finding that meaning,” Rodick writes, “a kind of alternative meaning comes about, one based more on bearing witness to this conundrum, on observing that the journey returns to the center as opposed to finding its destination, which existed only in our imagination.”

text copyright 2009 Katherine Ware